f-architecture on (Political) Labor and Its Refusal

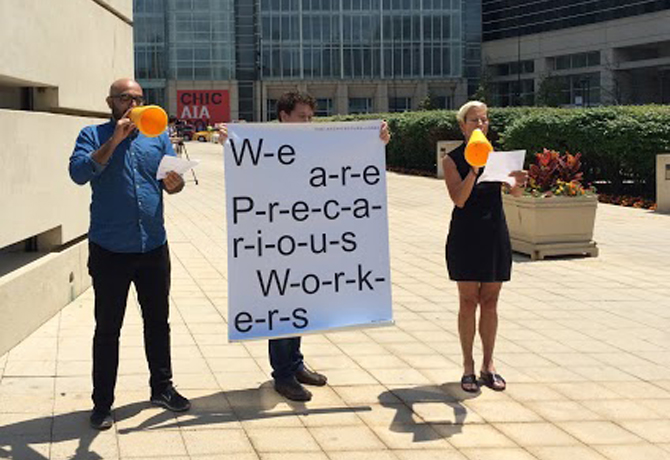

By Gabrielle Printz [Above: solidarity rally at Washington Square Park for the National General Strike on February 17th]

Protest is rarely simple objection. It is a pro-active practice and enterprise that requires intense organization, resources, and space. There’s the subway swipe to the site of demonstration, the privately-owned but public square where it’s held, the necessary permits for such an occupation, the week(s) of bureaucratic movement toward issuing that permit, the legal definitions that translate speech acts into the provision of space, the security forces that are paid to interpret, protect, and undermine that space and the bodies assembling there, what they are wearing (Nikes? Kevlar?), how they are armed, how they appear in the images that testify to demonstration and its message, the media platforms where those images circulate, where the call to assemble was fomented in the first place, and where hashtagged efforts amplify resistance and recirculate other calls to action…

We have invited these ancillary forms of protest that support political assembly, representation and will as a form of practice. These are not just the methods of occupation that overwhelm or undo the built, but the lighter and more agile efforts of spatial practice to sustain a public that needs architecture as it needs justice, equity, wifi and a cup of coffee, please. In our practice, we deploy design across the strata of media which enables the practice and presentation of architecture to also resist oppression, recognize inequity, embrace intersectionality, and submit new ideas to cultures political and architectural.

All that is to say, our labor is political, but more importantly, protest is itself laborious: it wears on the body, it requires more than some have to give, and it requires multiple tactics to prop itself up.

How to resist? Delete your account?

Strike!

I am writing this essay in advance of the General Strike planned for Friday, February 17th. Striking in place of protest was an idea floated by Francine Prose in an opinion piece that ran in the Guardian after the executive order restricting travel from a number of majority Muslim countries drove protesters to JFK and international airports around the country. Her argument credits those protests, but suggests that it is in fact more powerful to retreat from the market than it is to appear in the street (or terminal) en masse.

Withholding the economic power (of your labor and spending) might seem rather Leninist for 2017. But in the age of corporate entanglements and benevolent capitalism, boycotts by moralizing consumers have proven effective. And it’s also how corporations hold sway over government: capital exerts (political) power. By way of appeasement, the Uber CEO gives up his seat on Trump’s economic advisory council, but only after some 200,000 users had swung their votes to Lyft. Lyft had curried their favor by committing a million dollars to the ACLU, despite the fact that its major investor had actively supported Trump’s campaign and now advises the president on regulation.

Removing one app to support another reveals a litany of other nefarious entanglements and opportunities to make political choices with our Apple Wallets. We attempt to fight one head of the “capitalist hydra” with the brief satisfaction of releasing ourselves from a fraught indulgence. But in the void left by that one entanglement, another rears up with an uneasy proximity to Jared Kushner, to the occupation of Palestine, to a policy that denies lgbt+ rights.

Prose herself exited that opinion piece with a mention of the “not uncomplicated” pleasure of deleting her Uber account.

This form of conscious consumption has accompanied the “lean-in” feminism that presided over the women’s marches on January 21, the planning for which included the procurement of party buses and airbnbs, protest outfits, pussy hats, port-o-potties, and other materials and services to prop up the whole affair. Critiques of the march—of its embedded socioeconomics, its glaring whiteness, and its moments of trans-exclusivity—are important, and I won’t dwell on the fractures in a movement to unite many women and feminisms. But the mode and economy of assembly which produced millions of people at the marches on and beyond Washington are worthwhile considerations if such a movement is to continue. A general strike asks those women not to resource occupation, but to abstain from their presence in the formal labor market. It’s an action that solidifies the position of Sheryl Sandberg-types with those less readily acknowledged by mainstream feminism—that, together, we can all actively opt out, with consequence.

An essay co-authored by Linda Martín Alcoff, Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, Nancy Fraser, Barbara Ransby, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Rasmea Yousef Odeh, and Angela Davis again lobbied women’s marchers to commit to striking. The date they’ve nominated, March 8, is intentional: International Women’s Day is celebrated around the world, and in part commemorates a strike by Russian women garment workers that precipitated the events of the February 1917 revolution. Without the collective representation of a union or a coherent women's labor force, the authors ask women to disappear at once from their sites of compensated and uncompensated labor:

The idea is to mobilize women, including trans women, and all who support them in an international day of struggle – a day of striking, marching, blocking roads, bridges, and squares, abstaining from domestic care and sex work, boycotting, calling out misogynistic politicians and companies, striking in educational institutions. These actions are aimed at making visible the needs and aspirations of those whom lean-in feminism ignored: women in the formal labor market, women working in the sphere of social reproduction and care, and unemployed and precarious working women.

The striking of privileged and working women helps to recognize all those others who must engage in other forms of labor—informal, physical, domestic, reproductive, emotional¹—that shape both lives and markets.

A National Architects’ Strike?

Of course, architecture—the profession—enjoys no autonomy from these politics of labor and appearance. But when architecture invites the political, it tends to do so through objection rather than action, despite the existential predisposition felt by designers to make and do. Do we boycott the AIA conference that features no women keynotes? Rosa Sheng says no.² Do we refuse to design buildings for solitary confinement, torture or death? Raphael Sperry and Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility have been lobbying the AIA to amend the professional ethics code to refuse these projects since 2012. Architects won’t build your prison, your wall, by choice or code, but that doesn’t ensure they won’t be built. Perhaps due to the nature of conventional design work, architecture practitioners are ever caught between complicity and refusal—to render services, pay dues, or show up at all.

But as Stephen Zacks pointed out at the outset of this administration, architects as a united (or unionized) front could withhold their labor with great consequence to all that depends on building. “Construction,” he asserts, “represents $1.09 trillion of the U.S. economy, 6 percent of the total GDP in 2016, employing more than 6.3 million workers.”

The development of land and brand, the material appearances of capital as building, the provision of space for other productions of capital, and all the contracts and jobs that rely on such projects all presumably depend on the work of architects as the sole arbiters of space. But a profession-wide boycott in turn depends on a common definition of what architects with diverse relations to this thing we call the profession are and do. Would their work—if it is to realize buildings and built capital—carry on without them? by engineers and contractors with no such ethical obligations to human service and the betterment of the environment?

Even the AIA seems unable to assert a unifying definition of architect to adequately represent its members (not to mention those who forego membership). Instead, it adjudicates their professional conduct with clients. How might the organization be moved to take what some of its members see as a compromising position amongst other willing builders, especially if it can’t agree to censure architects for designing death chambers?

Work and resignation are feminist issues.

In the framework of a professional organization, collaboration and refusal scale from the institution to the individual. Cue the number of memberships given up after Robert Ivy announced the profession’s willing collaboration with the new administration. At this latter end, of individual boycott, we might better see the problematics—and the efficacy—of protest as refusal.

Sara Ahmed publicly withdrew from her position at Goldsmiths last year due to inaction on the problem of institutional sexism. In an essay accounting her reasons for leaving, she defends withdrawal as a feminist action among the political logics of staying (to fight) or leaving (to fight):

To work as a feminist means trying to transform the organisations that employ us – or house us. This rather obvious fact has some telling consequences. When we try to shake the walls of the house, we are also shaking the foundations of our own existence.

But what if we do this work and the walls stay up? What if we do this work and the same things keep coming up? What if our own work of exposing a problem is used as evidence there is no problem? Then you have to ask yourself: can I keep working here? What if staying employed by an institution means you have to agree to remain silent about what might damage its reputation?

By saying resignation is a feminist issue I am not saying to resign is an inherently feminist act even when you resign in protest because of the failure to deal with the problem sexual harassment. I am saying: to be a feminist at work means holding in suspense the question of where to do our work. The work you do must be what you question. Sometimes, leaving can be staying, with feminism. Sometimes. And not for all feminists: other feminists in the same situation might stay because they cannot afford to leave, or because they have not lost the will to keep chipping away at those walls.

Elsewhere in her writing on sexism, Ahmed cites a particular form of exhaustion: that what may prevent further action against cultures of sexism is the continual labor of calling it out. In the introduction to a special issue of New Formations, “Sexism—A Problem with a Name,” she writes:

...sexism might drop out of the feminist vocabulary not because of our success in transforming disciplines but because of the exhaustion of having to keep struggling to transform disciplines. It might be because of sexism that we do not attend to sexism. We lose the word; keep the thing.

So there is value and necessity in staying, too. But exhaustion is added to slate of feelings we are conditioned to avoid as feminists engaged in such a struggle. In the political arena of participation, women interlocutors are compelled to overcome their frustration and exhaustion, especially in the settings where men still maintain authority. Instead of disrupting a thing we can identify as sexist, we are expected to be more positive, agreeable, and constructive: to build a reality in place of or alongside the one that already demands our labor, to offer alternatives, and all without resorting to joy-killing critique.³ Between her two texts, we can see Ahmed as weighing her own act of refusal against a struggle we cannot retreat from. It takes a sustained and “conscious willed effort” not to reproduce the political reality of sexism or racism. But through her resignation, we also see that negation or refusal isn’t altogether a retreat from this struggle, and certainly not less effective or urgent than positive action. As Audre Lorde reminds us, respite from this space of political labor is not retreat: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.”ª Ahmed embraces her position as feminist killjoy in life and work, and like her, we exercise particular forms of denial that allow us to continue to attend to endemic issues and to hurry the slow creep of progress (no Santiago Calatrava, we can’t wait a second).

How do you strike as an “activist practice”?

When your labor is itself political, when do you withhold it?

I don’t know, I’m asking you.

I mean, we still went to the rally instead of writing or drawing or sending emails on Friday. But it seems pointless to ask which activities are more worthwhile if they also act to undo sexism, build more just environments, or make arguments that advance social causes. It is worthwhile to examine the instances in which doing and not doing are most meaningful. Of course we need all these tactics, to refuse and to do, and in ever more nuanced ways. Yes we will boycott. No we will not tolerate discrimination. No we will not contribute to architectures of exclusion. Yes we will work to undo those actions. No we will not leave. Yes we will continue to struggle. And when that struggle has stalled, we will resist from other positions, with new tactics, and more partners in protest. The instantiation of this implicit “we” is not the last or first in a series of actions, but also a continual enterprise: Does this organization/profession/institution adequately represent our concerns? How do we change it? What members need to be better represented? Do we remove ourselves and form new constitutions with other collaborators?

¹ A widely circulated 2015 metafilter thread accounting the forms and effects of emotional labor is now available in condensed form.

² “Boycotting the conference doesn't solve the problem of inclusion or representation,” Rosa Sheng responds to a comment on what she sees as Architect’s Newspaper’s indulgence in outrage, https://archpaper.com/2017/02/2017-aia-convention-women-architect-keynote/.

³ Ahmed identifies in the same text where this retreat from critique pops up in feminist theory, with a quote from Elizabeth Grosz: “But if [feminist theory] remains simply reactive, simply a critique, it ultimately affirms the theories it wishes to move beyond. It necessarily remains on the ground it aims to contest…coupled with this negative project must be a positive constructive project, creating alternatives: producing feminist not simply anti-sexist theory.”

ª Audre Lorde, A Burst of Light: Essays (Ithaca, New York: Firebrand Books, 1988), 131.

f-architecture (alt: feminist architecture collaborative) is a three-woman research enterprise aimed at disentangling the contemporary spatial politics and technological appearances of bodies, intimately and globally. Partners/caryatids/bffs Gabrielle Printz, Virginia Black and Rosana Elkhatib run their practice out of the GSAPP Incubator at NEW INC, an initiative of the New Museum.