Intuition and Humor: Lorena Del Rio on Facing Her Fears

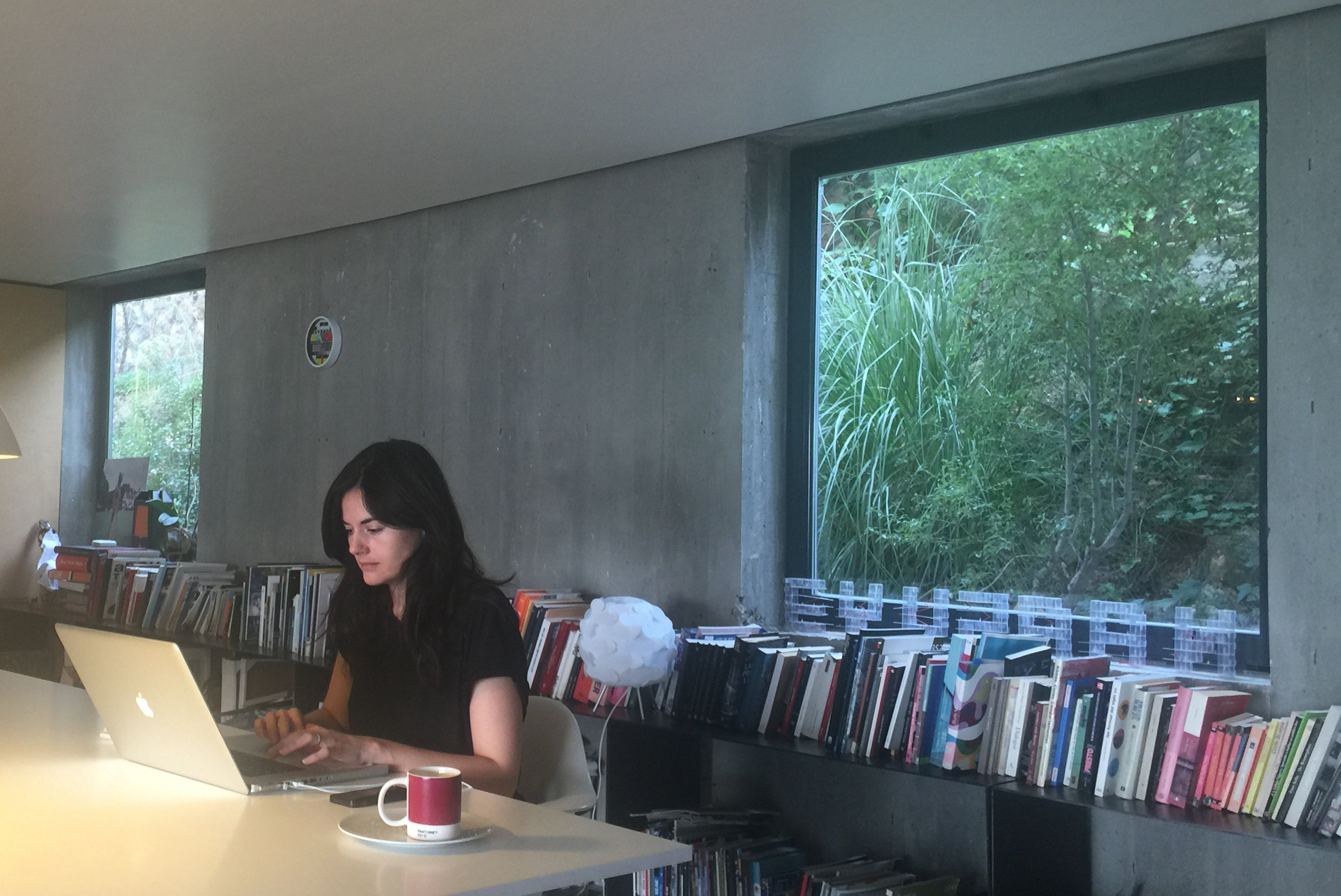

By Julia Gamolina Lorena del Río is an architect, co-founder of RICA* STUDIO based in New York and Madrid, and an Assistant Professor at the Cooper Union. Her academic research stems from an interdisciplinary approach to design where architecture, art, and material research meet to promote emotional well-being. Lorena is educated at the Polytechnic University of Madrid, ETSAM, where she is also developing a PhD focusing on the sensuality of materials. Prior to founding RICA* STUDIO together with Iñaqui Carnicero, she was a senior architect at SelgasCano. Lorena has taught at Cornell University as a Visiting Assistant Professor and California College of the Arts, where she also was the co-director of the BuildLab. In her conversation with Julia Gamolina, Lorena describes her incredibly rich career, working with her partner, and new beginnings. She also speaks to her intuitive approach in stepping out of her comfort zone, and advises young architects to find what they love and never give up.

JG: How did your interest in architecture develop?

LDR: My parents owned an antiques store, so I was familiar with interiors, furniture, and objects since I was little. I thought I wanted to study interior design, but my intuition told me to go into something more technical. After my first year in architecture, I did fall in love with the technical aspects, especially with ways of challenging conventions. I also loved that an architect never works in isolation - it’s a profession that engages many other disciplines.

Straight out of architecture school, you worked for one of Spain’s most creative firms: SelgasCano. What was it like and what did you learn?

SelgasCano is a very special and unique office – run by a couple, Jose Selgas and Lucia Cano. When I first came for my interview and saw their space, I thought, “These guys are so cool!” In the interview, Jose asked me what kind of music I liked. For them, these things are important, because they incorporate so much outside of architecture in their work. I worked with them for five years and more than “knowledge” in a conventional way, I learned a way of being. They taught me how to look through different eyes at everything - nature, art, music, cinema – and to bring it all together. Everything informs architecture; a movie, a natural setting, or a piece of art can trigger an idea for a project. They taught how to practice architecture as a way of living.

Your interest in plastics developed there.

Yes - the partners were interested in materials that challenge the perception of gravity, create ethereal atmospheres, and deal with natural light in a new way. They use plastics in many different ways, they use a huge range of materials in general. I became interested not only in the technical qualities of plastics, but also in connecting materials to the architectural concept at the very beginning, and being able to seduce with materials. I decided to pursue my PhD in these topics, and to use plastics as my case study.

After SelgasCano, you started teaching at Cornell. How did this come about?

The crisis in Spain started to get worse and specifically affected architecture offices. My relationship with and the work at SelgasCano was fantastic – I loved seeing the auditorium in Cartagena open after working on it for five years - but after participating in all phases of different projects I felt that I had reached the top in the office and it was good timing to try something else. My husband Inaqui got an offer to teach at Cornell for a year. At first, I was planning to go to Ithaca to be a scholar and work intensively on my PhD. Then, I also applied to teach a seminar focused on my research, Introduction to Plastics, and ended up teaching at Cornell full time for four years.

What was the transition to teaching and to the United States like?

I was completely out of my comfort zone. The hardest thing was the language barrier - my English wasn’t like it is now, and it was difficult for me to communicate. I felt insecure about using the wrong grammar or the wrong vocabulary in front of my students. I was good at pretending I wasn’t frustrated by it but I really was [laughs]. I also had no idea what a seminar meant in American academia; I just presented my experience, without having anything to reference it against. Now I know that by teaching in a different way, I was able to bring something new.

How did you cope with it?

By being patient and doing things the best way I knew how. I learned we should be able to make fun of ourselves; I remember saying things wrong in the first classes I taught at Cornell, and thankfully I was able to laugh and move on. I realized that it’s normal and it’s not about how you say things - it’s the type of things you say.

I also had a lot of encouragement. Andrea Simitch at Cornell always said to me, “You have a lot to offer.” It was good to hear this from a woman who was also once a very young professor and one of the few women at Cornell. She really helped me by making me feel that I could do it and I could do it well, and that the things I offered were different, and were great because they were different.

You are now one of the first two tenure-track professors at the Cooper Union in almost three decades. How does it feel!

It’s very exciting and also unbelievable - I know many people applied for the position. The application process was a real challenge but also a real honor; in addition to having one of the most prestigious architecture programs in America, Cooper Union has the perfect balance between the size of the school, the intensity of the work, the amazing professors, and also the interdisciplinary approach. This makes the students very unique.

Can you tell me about RICA Studio, the practice you run with Inaqui?

RICA from RIo-CArnicero– in Spanish it also means something tasty or good. You could say good food is rica; we liked that double meaning.

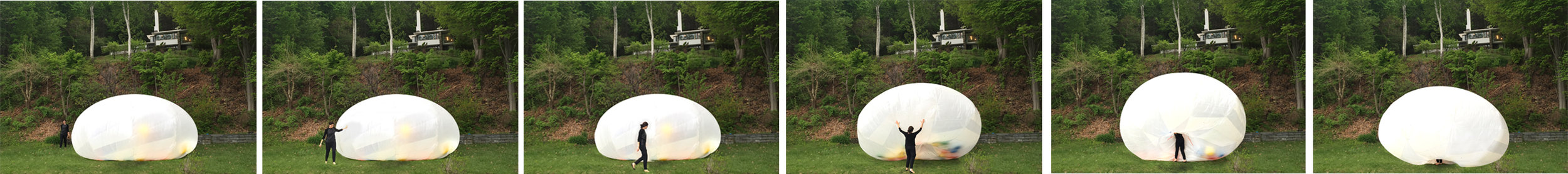

Our work is diverse. The Venice Biennale was huge for us - Inaqui was appointed the co-curator of the Spanish pavilion and RICA took the lead of the pavilion design. We received the Golden Lion, and are now adapting the exhibition to galleries around the world. Then, our private clients are giving us the opportunity to re-think the domestic space in several single family home commissions. We are also interested in challenging conventions in educational spaces, like in the project we recently completed to transform an existing building into a kindergarten. Finally, we love competitions; we maintain the routine of always having one on our desk as a way to engage with ideas in different cultural and social contexts.

Are the States and Spain different in terms of practice?

Radically. In Spain, the system of competitions is amazing. A young professional can get a big commission because it’s not about networking or about having a lot of experience - it’s about your value as a designer. As a result of mostly public competitions, we have amazing architecture in Spain. I always complain about the States not having that system because there are so many public buildings being built here without any design aspiration.

Is it possible to separate work from your home life?

We try but it’s not [laughs]. After working together intensively the last six years, we are now in our best moment and I can happily talk about how great it is to work with your partner. It wasn’t always like that [laughs]. At the beginning, Inaqui was expecting me to do things his way, and I was expecting him to do things my way. We realized that it’s about finding what he is really good at, and what I’m really good at. I go ahead, and he trusts me, and the other way around.

Working together does also have a bright side, like having important meetings with your partner in your pajamas, or Skyping at 2am from bed when coordinating with our Madrid office.

What have you taught each other?

For me, Inaqui is the bravest person in the world. He believes he can do anything, and he taught me to believe I can do anything as well. He said, “You have to apply to Selgascano - they’re going to love your work,” and he was right! As a student, I didn’t trust my skills and I wasn’t confident in myself. When I see how far I’ve come since then, and the amount of times I’ve faced my fears, I know I’ve grown a lot and Inaqui has had a big part in that.

On the other side, I am and always was very patient and Inaqui really was not. He needs to see things happening right away or he gets anxious. I have a view that’s more long-term, and I think I've taught him its benefits. He’s more patient and less anxious now for sure [laughs].

How does your teaching inform your practice?

There is so much intelligence gathered in a classroom at places like Cornell or the Cooper Union that can be applied to resolving real issues. I taught a course once where my students designed playgrounds and constructed full scale prototypes of them, based on a research we were developing at RICA. Then, I invited a local Montessori school to the final review, and the kids played in and tested the playgrounds. It was an extremely pedagogical experience.

What are some challenges that you’ve faced in your career?

When I was a student, I struggled with criticism and how to use feedback in a positive way. I wanted to do things right immediately, and that never happens in architecture – it’s all about persistence. I always convey to my students that they have to be strong and separate their feelings about themselves from the feedback their projects receive, because in the end, architecture is something beautiful. I also always knew that finding my place as an architect and a woman wouldn’t be easy; architecture is still a male profession.

What have been some highlights?

The results of our investigative process are always highlights. We truly believe in the power of design to change behavior and improve life conditions. In our project English for Fun, a kindergarten in Madrid, we were able to challenge and improve educational environments. For our collaboration with Juegaterapia, we designed a playground in a hospital for kids suffering from cancer. It’s fantastic when architecture goes beyond just building spaces, and affects well-being. Working with these kids was an incredible honor.

What has been your general approach to your career?

In terms of my work, the way architecture was taught to me was through the study of the masters and the production of architectural objects. For me, architecture actually has more to do with daily life - what we see, hear, feel, smell, the way we behave, nature. I try to incorporate sensorial experiences into my work and translate them into a physical space. My focus is seducing the senses through architecture.

In terms of my career, I never had a clear strategy - I was mostly guided by my intuition. I made decisions not because I was following a plan, but because I felt good about them. One rule I did have is to tell myself that I always need to enjoy what I’m doing and change whatever was needed in order to do work I really like. It's all about enjoyment.

What is the biggest lesson you’ve learned?

To never take things too seriously! I always rely on making jokes. When I first came to the States, my level of English wasn’t good enough to be funny, and that was really frustrating because jokes are a part of me and I always use humor as a way to relate to people.

Looking back, what are you most proud of?

I’m really proud of learning how to move out of my comfort zone without any fear. There is a saying in Spanish, “perfection is the enemy of good.” It’s true. You should aim to make things good, but not perfect, because if you aim to be perfect you can get lost in things that are not important. There are many ways to do things and perfection doesn't exist - it’s all about being satisfied with what you’re doing and trying to improve.

Academia can also be a harsh environment sometimes, and I’ve learned to navigate through competitiveness, criticism, and challenging colleagues. At this point I’ve been challenging myself for five straight years – presenting my work to the public, to students, to selection committees. I know now that I am what I am, not more and not less, and I just present what I am. Accepting myself as I am is one of the biggest hurdles I’ve overcome.

What advice would you give to young architects?

To be enthusiastic, to enjoy, and to never give up trying to do what you want to do. Architecture is really broad and there are many ways to find your place within the discipline. It’s all about finding your passion and your obsessions, and following your intuition. Architecture is something very intimate and connects with the most profound part of ourselves, so every young architect should find what they love most in the field and go for it.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://architexx.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/MA.jpg[/author_image] [author_info] With experience in design, business development, PR, and marketing, Julia Gamolina is focused on communicating identity in the built environment. She is a regular contributor to sub_texxt, interviewing women in architecture on their career development. She is also on the Young Leader's Group committee for the Urban Land Institute (ULI), and is a Founding Member of the Wing. Julia received her Bachelor of Architecture at Cornell University, graduating with the Charles Goodwin Sands Memorial Medal for exceptional merit in the thesis of architecture.[/author_info] [/author]