Michele Gorman's This is My House of Green Grass: The Raw Retrieval of the Civil War

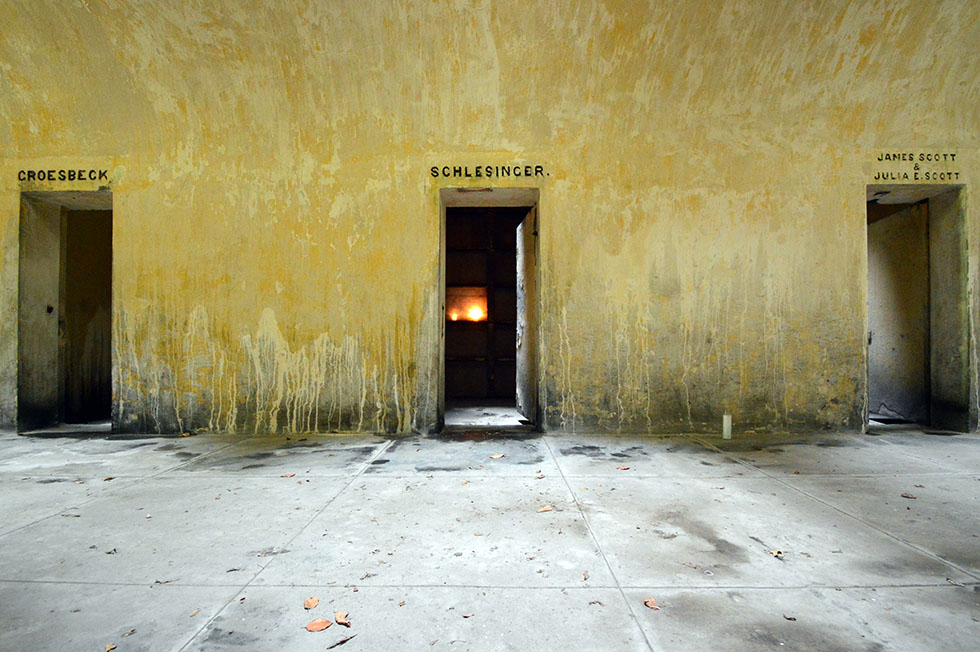

Photography by Ashley Simone The weekend of May 23, 2015, Green-Wood Cemetery commemorated the 150th anniversary of the Civil War with a variety of exhibitions and events honoring this important period in American history. One such program was the installation of This is My House of Green Grass: The Raw Retrieval of the Civil War, a data visualization “happening” by architect-artist Michele Gorman. Installed in Green-Wood’s historic catacombs, This is My House of Green Grass was a visual analysis of the cemetery’s archive, synthesizing information about the five thousand soldiers, musicians, nurses, doctors, and abolitionists who now rest within Green-Wood’s 478 acres and represent New York City’s involvement in the Civil War.

For many years, Green-Wood officials thought that approximately 500 Civil War participants were buried at the cemetery. But recent research led by Green-Wood historian Jeff Richman reveals that there are more than 5,000 interred on the grounds. Richman’s large research team continues to uncover information about local involvement in the Civil War. The perennial question is, how to bring the public closer to the both the newly uncovered information and the landscape of the cemetery?

Gorman’s approach made use of her training in architecture to translate this archival data visually, spatially and acoustically. Early in 2015, Gorman approached Richman with the idea of developing interpretive strategies for his ongoing efforts to digitize all Green-Wood records, which will be ongoing through next year. Using light and sound installations strategically in the catacombs, Gorman sought to represent Richman’s research in new ways, to reveal new narratives about the Civil War victims and heroes and personal relationships between them. Utilizing the catacombs in a hillside deep in the cemetery, the slowly pulsing of lights of This is My House becomes a kind of heartbeat that gives new life to its history.

As a neighbor of Green-Wood, Gorman was interested in activating the cemetery as an escape from the fast, dense and hot spaces of the city. She saw the catacombs, particularly, as a place that engages the social history of the city, and evokes pre-urbanized landscapes. In Gorman’s words, “The site operates as a threshold that mediates the archival data and the burial ground. Contextualizing the research within the depths of the cemetery, as an alternative to a museum or gallery, for example, was a critical element of the project for me.”

My House of Green Grass takes its title from the German folk poem, “Where the Fair Trumpets Sound” about a soldier who died in war. In the story, the soldier speaks from the afterlife to his lover who is still grieving his early death. The communication between the dead and the living in this poem provided inspiration for the tone of the project: "Who then is outside and who is knocking, that can so softly awaken me? ... I’m off to war, on the green heath; the green heath is so far away! Where there the fair trumpets sound, there is my home, my house of green grass!"

Like Mahler’s grieving lover, Gorman’s installation awakens—visually, spatially, and acoustically—the life of the centuries-old archive within the dark corridors of the catacombs. In one installation, designed in conjunction with sound artists Alex Marse and Ben Rubin, a narration of text and numbers pulled directly from the Civil War data reckons with the causes and pace of deaths during and after the war years. On a screen suspended at the end of a vaulted corridor, projections scrolled through handwritten death index cards chronologically, flashing light with each passing year, slow drumbeats amplified based on the number and speed of the deaths. While displaying data from 1862, at the height of the Civil War, the beats sounded like a racing a heart. A multitude of nationalities, ages and familiar New York City addresses flashed by on the lines of the index cards, showing obvious causes of death during the war years– “killed in action”, “battle wounds”, and “typhoid fever”–fifteen years later, deaths are still related to the extreme circumstances the participants went through. “Consumption”, “dysentery”, “pleurisy”, and “skin cancer” were lasting effects of war that did not end with the war itself in 1865.

The result was a re-imagining of the archive, both spatially and sonically, that creates a new virtual landscape made of light, text and sound – a completely new way to see and experience archival data and historic research.

The main installation occupied the end of the dark, long and narrow corridor of the catacombs. Along the narrow hall, light streams through skylights in the vaulted ceiling through to the earth above.

The light traveled down the long, narrow corridor—colors washed the walls, fading in and out. The space came alive.

One scene in the projection extracts all of the body parts (nouns) that relate to the cause of death listed in the cemetery records. A male and female voice narrated the cemetery records showing causes of death that relate to specific body parts, with “of the” preceding the noun. Their voices projected from two catacomb cells facing each other, their voices, stretching into slow drone sounds, reverberated through the Catacombs’ chambers. And the cemetery records show not only the cause of death for each internment, but also biographical information and profession of the deceased, relating the effects on the body to the rank and role played in the war and in civilian life afterwards.

The final scene, by one of the five additional digital artist collaborations invited by Gorman, Zhen Liu and Eozin Che, uses the geographical location of the Civil War veteran's graves within the cemetery to create a virtual map of these souls within Green-Wood. Each burial is shown as a point of light on a map of the cemetery. The map is 3D, and points of light are situated differently based on rank and birthplace. All soldiers with the rank of First Lieutenants and Captains from Brooklyn, are elevated from the other burials. Through this organization, we can see a social topography emerging as glowing nodes display relationships to each other and the organization of the cemetery as a whole.

Since the project digitized and transposed the information of the 5,000 interred Civil War participants, Green-Wood has begun to the long process towards digitizing the entirety of cemetery records, including genealogical information family correspondence, burial orders, lot records, and affidavit records. As the archive is built, Green-Wood hopes to continue its translation into visual art installations. This important and compelling work will create continued opportunities for alternative readings of the vast landscape of data held in the cemetery and foster a re-imagining of historic research.

[embed]https://vimeo.com/129828189[/embed]

Written/Edited by Michele Gorman, Chelsea Dowell, Ashley Simone, Sarah Rafson, Jenny Florence

All photography is © Ashley Simone, unless otherwise noted.