Redefining Success: A Conversation with Irina Schneid

By Julia Gamolina Irina Schneid is a registered architect, adjunct assistant professor, founder and principal of SCH+ARC Studio, and a new mother. Based in New York, Irina has lectured and taught internationally. Recent appointments include Barnard and Columbia Colleges’ Department of Architecture, Pratt Institute, Temple University, and the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) in Melbourne, Australia.

Having recently launched her own design practice while teaching, writing, and mentoring, we were thrilled to learn she was adding motherhood to her already long list of accomplishments. Interviewed by Julia Gamolina, her longtime friend and mentee back from their Cornell years, we sought to find out how Irina achieves balance, establishes priorities, and makes everything that is important to her, work.

Not long out of school, you’ve already earned an advanced degree and an architecture license, started a firm, and become an adjunct professor and a mother. Were these always your goals or did these aspects of your career come together organically?

Teaching and motherhood have been driving forces in my career. The architectural license and advanced degree were tools to get me there. I knew from early on in my design education that it would be difficult to balance having a family and a profession in architecture. I set myself the goal of becoming licensed prior to having a child as a way to ensure my employability following any time off I’d plan to take for maternity leave. The license would enable me to work again; it would keep my head in the game, and serve as a key with which to reenter the work force. The advanced degree was essential in laying the foundation for my teaching career; giving me the time to develop my pedagogical interests and the space to test them out.

What have you learned by having all these things come together?

I’ve learned that there is an inherent risk in listing career goals as bullet points on a to-do list. It’s one thing to have functionally established a practice and an entirely different thing to sustain it as a successful venture. I am at the point now where I have mechanically laid the groundwork for SCH+ARC Studio, and recognize that I am going to have to push twice as hard to achieve my vision for it.

When did you realize you wanted to teach?

As an undergraduate thesis student I was invited to sit on the final review jury of a design studio co-taught by Mark Morris and Daniel Libeskind. I was the only woman, the only student on a jury led by a world renowned architect, in a packed, standing room-only gallery. I felt empowered. For the first time in my academic career I was given the opportunity to provide constructive feedback, to be taken seriously, and I ran with it. By the end of that review I knew that nothing would satisfy my design hunger as much as teaching would.

How did you transition into teaching?

Shortly after completing my M.Arch II degree at Cornell University, my husband and I relocated to Melbourne, Australia, where I gave myself the year to gain a foothold in teaching. I started off by leading a discussion section for an introductory theory course at RMIT University. By the second term I had pitched a syllabus for a graduate design studio and was selected to teach it.

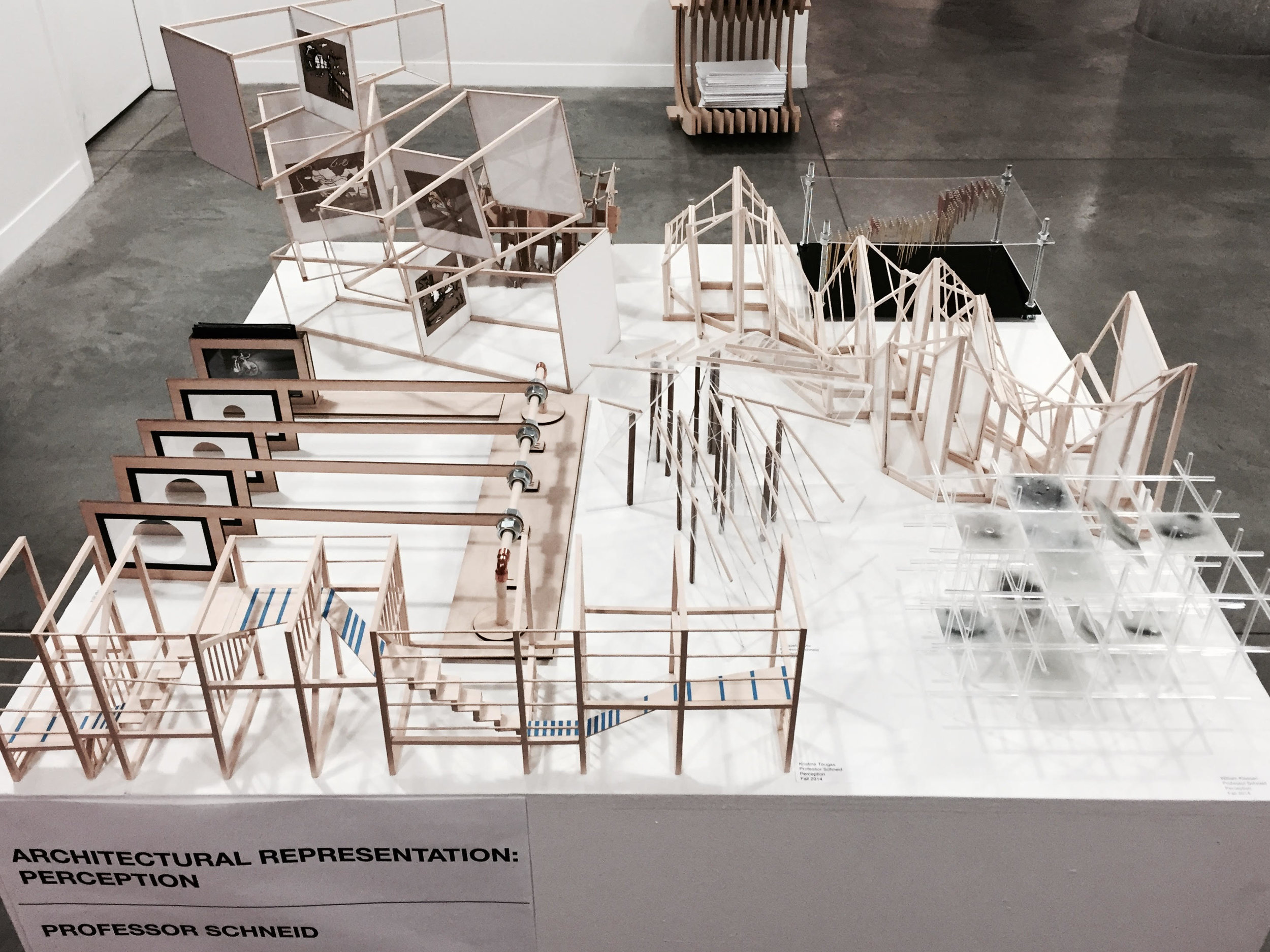

Upon returning to the States and going back to my work at a New York-based design studio, I realized that while my job had stayed the same, my priorities had shifted. My passion was teaching and I needed to refocus my energy on pursuing it. By the beginning of the next school year I was teaching four courses in three universities across two states. The work was challenging and the commute was exhausting, but I loved it. I love to formulate questions that put seemingly familiar concepts on their heads. I love exposing students to new technologies and showing them new ways of using the ones they already know.

What are your learning objectives for your students?

I’m at an interesting point in my career where I’m simultaneously teaching introductory and senior design studios. My focus when working with first-year students is not on teaching them how to become architects, but rather, on training them to think like architects; to look at the world differently, to analyze, abstract, to learn through making.

At the same time, I want to equip my thesis students with the tools necessary to define their own agenda, methodology, and definition of practice. I urge them to look back and take stock of their student experience such that they can look ahead and identify what scale and scope of work they want to engage in, what types of problems they want to solve, what drives them, and how far.

Has your career trajectory been affected by your desire to become a mother?

Prior to my transition into teaching and starting my own practice, I worked design studio hours that would be impossible for a mother to sustain. I tracked the retention rate of female employees as they approached motherhood and plotted my own trajectory five, ten years down the line. I felt that no matter the professional circumstance, for me, motherhood would be a constant. And so I had to reframe my career path knowing that although I would never want to stop working, I had to make it work for me.

How has motherhood changed your own notion of success in architecture?

Motherhood has liberated me from the pressure I put on myself to always be chasing after success. The goal I set for myself every day is to be present for my daughter. I feel her infancy slipping from under my fingers, and right now, I want nothing more than to catch it—in real time.

I would never have thought that motherhood would fulfill me in the ways that it does. I have always been an extremely career-driven person. But there was a point in my life when I did not know how to dwell in success without having a project on the horizon or a game plan for what comes next. It is a radical shift in mindset to live in the moment rather than two steps ahead. The realization that I am in control of my own timeline rather than subject to it, and that I can set the pace for my future rather than always be running after it—that is my redefinition of success.

As someone just returning to work after maternity leave, what are your thoughts on our industry’s attitude towards motherhood?

Our industry’s expectations, hours, facilities, benefits, and pay are all skewed towards the childless worker. Motherhood is often seen as an obstacle, as something an employee needs to overcome, persevere through, or recuperate from.

Many women are unprotected by law from the risk of losing their jobs because the studios they work for are not large enough to fall under its jurisdiction. 95% of architecture studios are exempt from the Family Medical Leave Act as they have fifty employees or fewer. Those that are large enough fail to provide appropriate pumping facilities (which take up less space than a large format printer) to make the transition back to work easier for women who are nursing. Flexible work arrangements are made difficult by the industry’s legacy of unrelenting work hours.

These factors make it challenging for mothers to retain any sense of work-life balance, often forcing them to choose one over the other. As an industry we can take the steps necessary to keep women in the field, to embrace the changes that parenthood brings to a worker, to capitalize on their new outlook rather than marginalize their needs.

Now you have the chance to lead by example and shape a new image for practice. Can you talk about your vision and internship plans for SCH+ARC Studio?

I see my practice as an extension of my teaching. It is a platform to carry out the questions and initiatives that arise within (and are typically confined to) the walls of academia. SCH+ARC’s internship program, WRKSHP, strives to do just that—to rethink the leap from academia into professional practice.

WRKSHP enables students to pitch and develop design projects of their choosing as part of a professional design fellowship with the studio. Fellows are provided with project management and career mentorship. They are given access to training in digital modeling, portfolio layout, and fabrication. Our beta projects ranged in scale from publications to playscapes, and tested prototypes in research labs across New York City. Moving forward, my vision for SCH+ARC is to interweave the investigations that the studio and its fellows pursue, allowing them to drive one another as a co-operative model for the future of architectural design practice.

Why did you get involved with ArchiteXX?

I saw ArchiteXX as a place where I could seek mentorship myself while expanding my own outreach.

In particular, I wanted to become more involved in university lecture planning. I saw ArchiteXX University Hubs as a platform I could help build to equip students with mentors beyond their immediate female faculty. I am proud of the work we have done so far. Our brown bag lecture series has created an outlet to bring female practitioners into classrooms to speak about their experience, not just about their work. The series takes the formality out of the traditional lecturer-student pedagogical model, opting instead for an open platform to ask questions and seek advice. It humanizes the profession to students who know it only through stylized renderings plastering the covers of magazines and blog feeds.

You were a crucial member of the team that did a fantastic job shaping the Public Choices Private Spaces exhibition. How has ArchiteXX influenced your experience with women in architecture? How has your thinking about the discipline evolved?

Through ArchiteXX I have met an inspirational group of practitioners who have joined forces to bring important issues to the heart of the architectural debate. I often tell my students that we must use design to drive change. Architecture houses, it shelters, it protects. It can empower or it can hold back. It can include as easily as it can exclude. As architects we must harness this power and use it to better the lives of those affected by our work, be it our occupants, our onlookers, or ourselves. We, women designers, can no longer wait for someone else to bring up issues which we think about but do not vocalize, which matter most to us yet remain on the back burner. Initiatives such as the Public Choices Private Spaces exhibition give credence to the female perspective. They strive to make so-called "women’s issues" into issues the discipline as a whole must address.

Julia Gamolina is a New York City-based designer, writer, and illustrator. Her academic and professional work focus on branding and identity, with a current focus on workplace design. She is a Project Manager at A+I and is interested in the career development of women in architecture.

Irina Schneid can be reached at ischneid@scharcstudio.com.