Space, Time, and Architecture: An Interview with Christina Ciardullo

Interview by Christopher Ball and Adam Kor While most architects seek out earthly sites, Christina Ciardullo looks to the stars and imagines what building on Mars might look like. Bringing humanism to the scientific world of NASA, Ciardullo's work and teaching explores how the unforgiving climes of Mars might support not just people, but poetics.

Christopher Ball: Having worked in your research on Martian architecture as both an architect and an educator on interdisciplinary teams—often composed largely of scientists—what are some of the opportunities and challenges that you’ve found?

Christina Ciardullo: It’s been strange working in these alternative contexts, as in traditional practice it’s the architect that typically functions as the coordinator, managing entire teams. In these highly specialized, technical fields however, you’re seen as an outsider whose main skill is to do renderings and present ideas to the outside world. Because it would be impossible to even approach the level of knowledge that these specialists have, as the generalist, the biggest challenge for me was grappling with my naiveté, in a good way. There is value in what architects bring to the table—we’re more apt to take risks, suggest things that seem impossible, and offer a humanistic perspective, but articulating and convincing a technical crowd of your value is the major hurdle to these types of collaborations.

In space exploration, it’s essential for the person leading the mission to understand that they are going there for particular reasons that are innately humanistic in addition to scientific. In my experience, it is only by keeping the broader picture in mind of why we’re exploring space that we can then properly understand what the mission should look like. An architect who works at Jet Propulsion Lab told our studio that while engineers are great problem solvers who can build to any number of requirements, it’s architects who write the requirements. For the interdisciplinary course I’m teaching this semester at Carnegie Mellon, a similar dynamic is coming out: the engineers and scientists are amazing at what they do, but we spent some time waiting to define the requirements, and it was the architects that jumped into that role more easily.

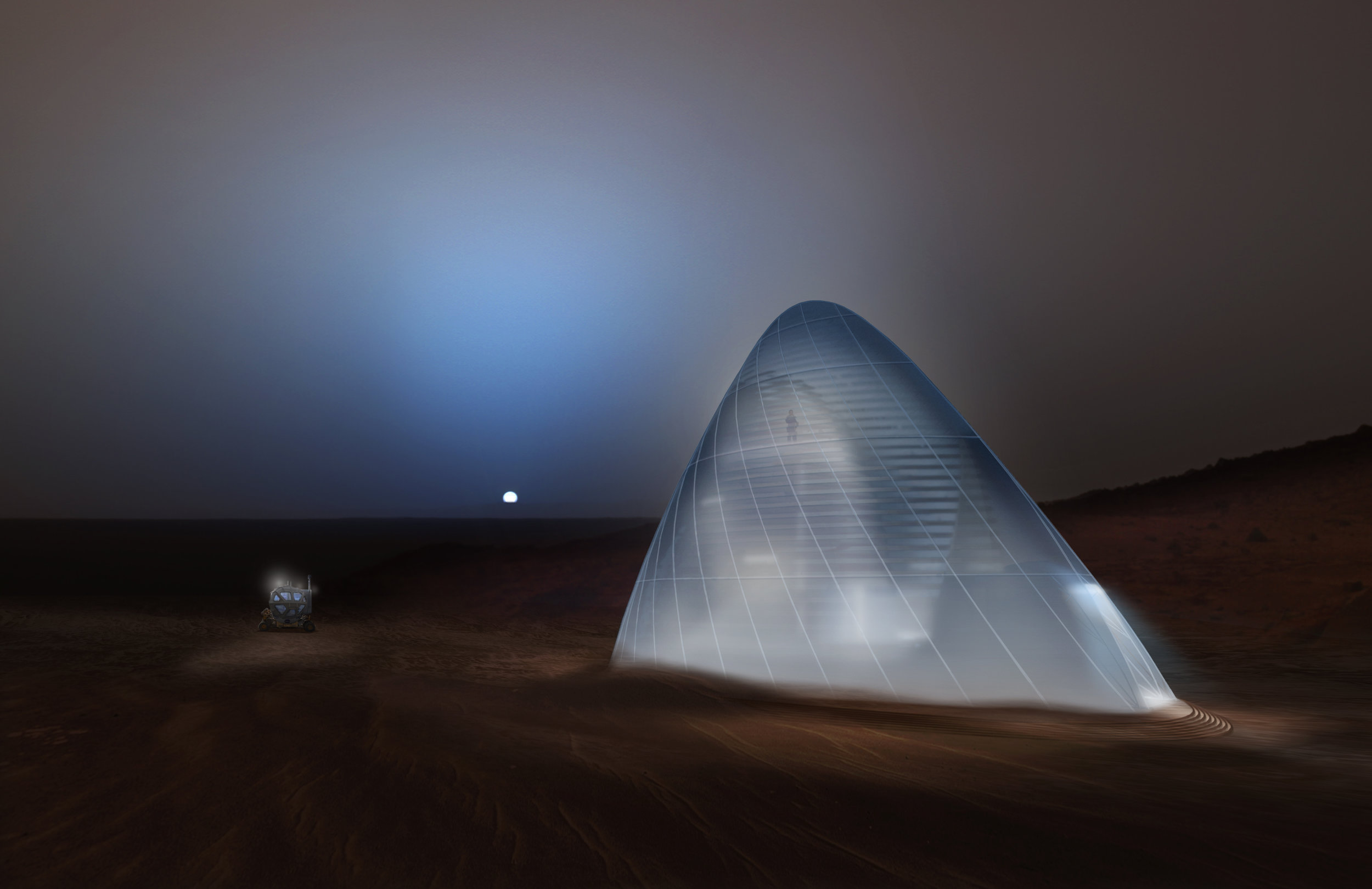

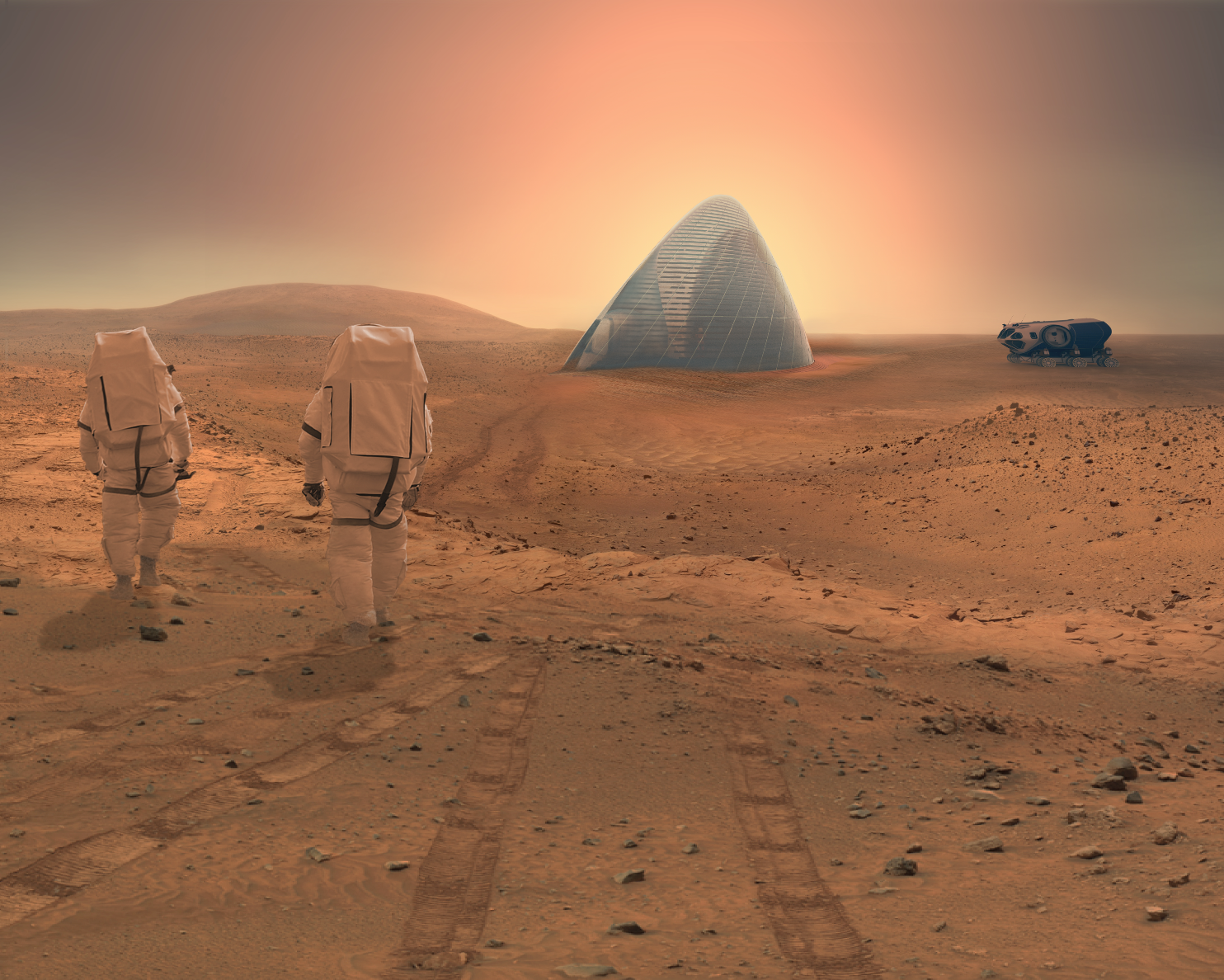

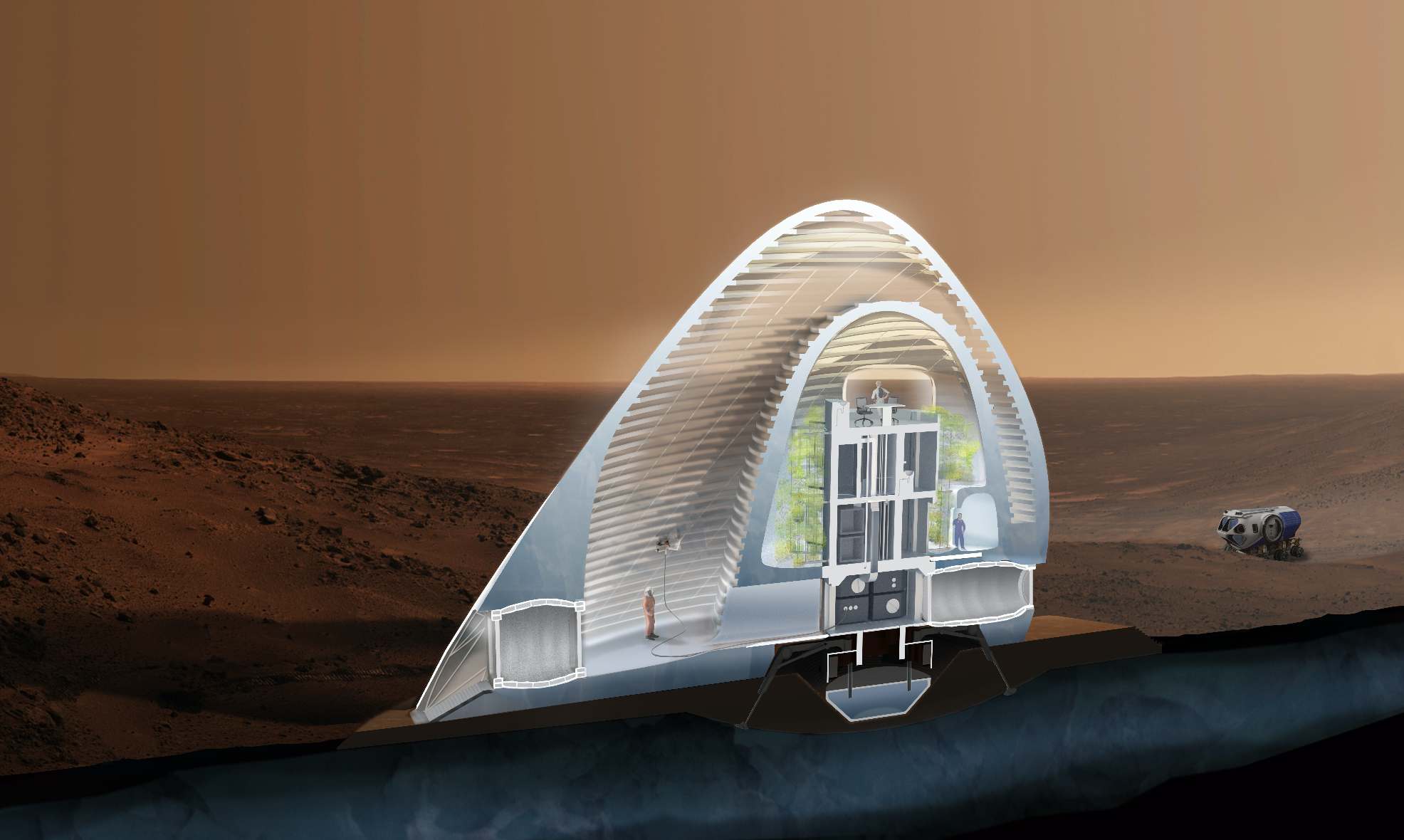

Adam Kor: Did you encounter these issues when working on your design proposal, the Ice House, for NASA’s 3D-Printed Habitat Challenge for Mars?

CC: The requirements for that competition were pretty strict. They didn’t want you to design a building larger than one thousand square feet because that’s all they can control with their life-support systems. Of course in many competitions, it’s often the team that rethinks the rules that ends up winning. In that sense, I think it would be an interesting competition for architects to come up with a brief and requirements. We should approach space exploration from a humanistic perspective—for example, defining the goals associated with what we’re trying to do—and write the requirements with that in mind, as opposed to trying to fit the design into a set of rules we’re not even sure works in the first place. I would love to get to a point where we, as architects and designers, can interject our thoughts earlier in the mission concept process.

CB: How have these issues manifest themselves in your work as an educator? For example, with regards to your Mars Studio, what are some of the differences between working as a part an interdisciplinary team and teaching an interdisciplinary class?

CC: It’s a big experiment, and it’s really exciting. I’ve never taken an interdisciplinary class like the one I’m teaching now myself. When I went to the International Space University, we did a team project, but I ultimately acted as the publicist in charge of the presentation and the visuals. Here, in the studio and classes I’m teaching at CMU, since we are acting under the umbrella of the architecture school, the role of the architect immediately takes on a certain importance, setting up for the architect to act as a manager in the way that is more typical to traditional practice.

CB: As an educator, what attitude do you bring to your teaching? As you mentioned, much of teaching is an open experiment of sorts, so how do you encourage your students to have personal agency in what they’re doing? And more generally, how do you work with and teach students who might have different interests than your own?

CC: That’s a really good question. It’s a two-way street—you have to assume that students are willing to take on a certain amount of responsibility in order for you to be able to open up that freedom. I want my students to have as much agency as possible, and so I’ve let them make up their own deliverables as one example, giving them the responsibility to say, “In order to achieve this project, these are the things that I need to make.”

I believe that when you directly choose your own projects, there’s something inside of you that motivates you to create these things, whether you get a grade for the project or not. In my studio, I’ve decided to keep the architectural program open and that has led to serious debate among my peers. Do I say that the project is to design a habitat for five people that functions a certain way, or do I let the students explore what a human presence should be with no bias on form or solution? It takes more time from the semester, but I think by allowing students to explore their own program—to question why are we going to Mars in the first place—they will find their own missions in doing the project, and hopefully, the project then reflects their own interests. Be it through a project on human-body evolution or 3D-printing, through choosing what they explore, they gain agency. There’s more room for error, but I think it also can lead to things that we’ve never imagined.

AK: You recently presented your work on Martian architecture at the conference, “Closed Worlds: Encounters That Never Happened,” organized by the Storefront for Art and Architecture and the Cooper Union. Touching upon what you presented there, how do you think this research on closed systems and building in extreme environments is relevant to and can inform more traditional modes of practice?

CC: I often like to show the difference between two different drawings talking about very similar things: a generic building sustainability diagram, with sunshine rays, wavy wind arrows, heat radiants, etc., versus the International Space Station life cycle diagram showing complex water and waste recycling, and air exchange. They are both very similar situations, but all too often in Earth architecture, these sustainable systems seem like add-ons. Out in space, you can’t survive without this stuff—it becomes essential to the proposal and the basis on which the architecture is built. I think there is a lot to be learned from this. When it’s so necessary for survival, you don’t take these systems for granted anymore. It gives you a greater sense of what your environment is providing for you on Earth, and it forces you to become more aware of the systems necessary to live in the way we do.

CB: The conference was also interesting because it talked about the parallels in architectural history. The concept of an “architectural closed system” has a long history but it doesn’t really have any built precedents. How does that history inform your work? Do you look back to those experiments in the ‘60s as inspiration when designing for outer space?

CC: The 1960s was a time of nuclear power and space exploration, and a time of great prosperity. That prosperity allowed us a kind of optimistic imagination and ambition, and as a result, much of the visionary architecture of the time touched on ideas of utopia. But the idea of utopia itself is often dystopic. If you design systems to function in enclosed worlds, it often has to be quite managed and rigid. Although they appear to approach perfection, they present an image of authoritarian control without freedom. Thinking of visionary architecture today, how can we continue to have passion, imagination, and hope for the future without resorting to these dystopic systems of the past? I think one good example is something like a living machine with plants and bacteria for filtration systems in the place of larger wastewater infrastructures. This approach can extend to other systems: we should try to find ways to let systems and architecture evolve and grow naturally, rather than controlling every step of the way.

CB: The precedents of that era make me think of the architecture of bubbles: Haus-Rucker-Co, Ant Farm, and Buckminster Fuller. As you mentioned, architecture in space needs to be self-sustaining and extremely predictable because you really can’t leave things open to chance. At the same time however, from a humanist perspective, that’s extremely limiting to personal freedom and agency. How do you design for chance in a system where there really isn’t any degree of tolerance?

CC: One of the biggest concerns of long-term missions is actually boredom. Everything is pretty regular—almost as if you looked at your iPhone and it said it was 72 degrees and sunny every single day. It would be nice, but there would be nothing interjecting into the system to cause you to be scared for your life. We live with an incredible amount of chance every day on Earth, and while it is morbid to say, we can die at any minute—and that actually may be a necessity for life. There is a large degree of randomness because our system on Earth is not closed, allowing for much more fluidity. The interesting difference between the super strict closed systems and freedom is excess. On Earth, we have a lot of buffer zones: oceans and atmospheres and people capable of maintaining the overall system despite all the things that go wrong, so there is a certain amount of freedom in excess. How do you allow for freedom and chance in space? Do you just build a system on Mars of excess? Do provide for more than you need to allow room for the system to fail and to grow? I don’t know the answer to that.

CB: Living on Mars or in space, architecture literally becomes your entire environment and the only thing you experience. In this case, what is the limit between architecture and the human experience?

CC: To survive in space, humans need oxygen, water, energy, and sufficient pressure on our bodies. These are things we need from our environment that our bodies can’t provide. Assuming our skin is the boundary between our self and the environment, on Mars we will never be able to be outside: we will always have something around us and will always be inside some architecture. As a result, our visual connection to the landscape becomes our only interaction with the environment. Because our system operates based on inputs and outputs, architecture becomes the medium, the definite boundary between ourselves and the outside: we need other materials to convey water, oxygen, and energy for us. If we could somehow evolve to incorporate energy and waste recycling inside our bodies, could we change the needs of architecture? Could our bodies become biologically engineered self-sustaining machines? What else is the role of architecture then? Or do we just leave our bodies on Earth and send out robots as extensions of our sense? It quickly becomes very existential.

CB: With regards to the idea that maintaining human psychology is just as important to life as the physical support system, how do you begin to design for that?

CC: This is a really big question—NASA also takes it seriously. We can understand the human body and its needs in a very scientific way, but we can’t quite capture everything about human psychology… unless of course you go to the psychology department, they can tell you exactly how we work!

But jokes aside, I don’t think there is—and I might be totally wrong—a measured scientific correlation between psychology, human behavior and architectural space. We certainly say all the time in architecture school that space changes people and affects their behavior, but if we really understood that in a scientific way, in the same way psychologists measure other environmental effects on human behavior, would we then have a clear answer to what architectural space for any particular program should look like? Is chance simply another factor to consider as a part of human psychology? Can it be designed into the system? Would things then become so predictable and regimented at a certain level that we wouldn’t be able to perceive our freedom because we would control our psychology so much with our environment? It’s a slippery slope. This is where my philosophy background leaves me paralyzed. If we can measure, document, and understand scientifically how human psychology and the human body relate to space in a very measured way, what then is left for the architect? Are we human factors engineers? Social engineers? Structural engineers? Artists? Is beauty just another factor to human psychology? Does architecture become about artistry or the agency of putting your mark on something? Thinking about outer space brings up so many questions that I can’t answer.

CB: We’ve talked about questions of the self, the unknown and the meaning of life—it’s all very existential. With a BA in Philosophy and Astronomy, how has that background informed your interests and work in architecture?

CC: It’s certainly been influential in that it’s been paralyzing—I now question myself every step of the way. Philosophy as a whole has really forced me to question the fundamental validity of the statements I make and the assumptions they require. It’s paralyzing, because you can really never quite get to the bottom of anything. I don’t think I’ve ever written a philosophy paper with a definite conclusion.

Now how has that translated into architecture for me? It often comes up when designing that we really don’t know the answer to a lot of questions that arise. As a designer however, I think you have to create a world of assumptions for your project, taking inputs from your clients and your consultants to lay out the fundamental beliefs of a project and make sure that everybody is on board—because if your assumptions don’t hold up, your whole building and project collapse, both literally and figuratively. Understanding the assumptions that you are making has proven to be the most philosophical aspect of studying architecture for me.

CB: After having worked as a designer for Ennead Architects, you then quit your job to pursue ventures in Martian architecture, first consulting with Foster + Partners before starting your own group, SEArch. Having made bold career moves as a young woman in architecture, what advice would you give for those just starting out?

CC: I really risked a lot, and I don’t know if I would do it again. I’m still scared to death about the decisions I’ve made and yes, I made a lot of stupid mistakes along the way. At the same time however, if I hadn’t risked my livelihood, I wouldn’t be teaching this year, here at CMU. I wouldn’t have spoken at the “Closed Encounters” conference, and I wouldn’t be continuing to find the next steps.

The advice I would give people going forward? Don’t be as stupid as I was, quitting my job, because I don’t know where I’ll be tomorrow. But it’s important to understand that if you have a desire to achieve something, at some point you are going to have to give yourself the time and space to do it, whether that’s within an office or on your own. That might be scary, but if you don’t give yourself time to do it now, you won’t do it later. You can say that at every moment at your life. You also have to be ready to accept responsibility for the risks you take.

AK: After all, your interest in architecture and space is all about the unknown!

CC: It’s all existential. What am I doing here? What is my life about? All I know is that I have to do something.

A version of this article appears in inter•view, vol. 2 of inter•punct, a journal for architecture founded by students at Carnegie Mellon University.